Hepatitis is a general term to describe inflammation of the liver tissue. It can arise from several causes, although the most common cause is a viral infection. It presents a significant global public health challenge with 2.3 billion new infections each year and 1.4 million deaths annually, with 98% of deaths being attributable to hepatitis B and C. Additionally, about 5.5 million people worldwide with HIV are also co-infected with hepatitis B or C, which is a rising cause of mortality for the HIV patient group.

Despite this, hepatitis has been generally overlooked as a health priority until recently. Without significant intervention, rates of hepatitis B are estimated to remain stable and high across the next 50 years, whilst the rates of people infected with hepatitis C are expected to rise annually, despite the availability of an effective cure.

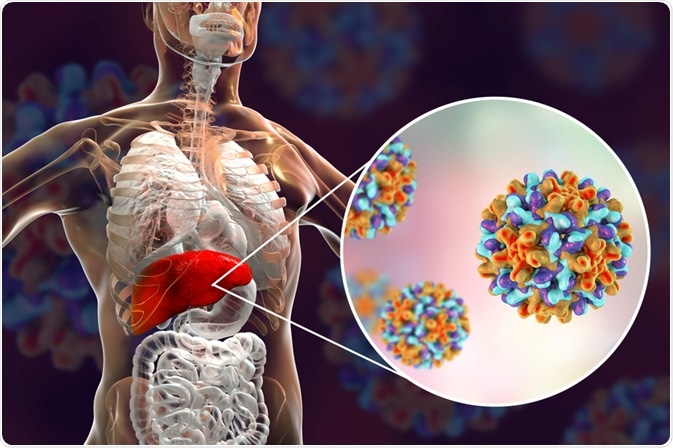

Hepatitis. Image Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

Targets to eliminate hepatitis

In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) endorsed the Global Health Sector Strategy to address the global disease burden of hepatitis. The strategy envisioned a halt to new infections of hepatitis B and C, and access to safe, affordable, and effective treatment for all. For the first-ever time, global targets for the elimination of hepatitis were established which included:

- From a baseline measure in 2015, a reduction of new cases of chronic hepatitis by 30% by 2020 and 90% by 2030. This represented a reduction in new cases from 6-10 million worldwide in 2015 to fewer than 1 million by 2030.

- To reduce mortality from hepatitis B and C by 10% by 2020 and 90% by 2030, representing a reduction in deaths from 1.4 million in 2015 to fewer than 500,000 by 2030.

How could viral hepatitis be eliminated?

The strategy document outlined five strategic directions, each comprised of critical actions that countries should undertake with support from WHO. These included:

- Gathering strategic information to understand the viral hepatitis epidemic, ensuring data is sufficiently detailed to identify ‘hotspots’ of infection, understand modes of transmission, and a—risk populations. Such information at a regional level should make deployment of interventions that are targeted and tailored, whilst ensuring interventions are aligned with existing services and health plans.

- Defining the evidence-based essential interventions that should be included in response to the epidemic, then the development of tailored national plans with appropriate governance and management to ensure they are embedded in services.

- Strengthening community and health systems to deliver high-quality and inclusive services, ensuring that those living with hepatitis and those at-risk have access to medical care. This should include defining the pathways to care at community, primary and tertiary care levels and integrating hepatitis services with pre-existing services, such as sexual health, cancer, and substance misuse services.

- Ensuring the strategy is underpinned by robust, equitable, and sustainable financial planning, by improving domestic tax collection, pooling funds across whole care systems, and improving efficiencies in healthcare.

- Promoting and incentivizing innovations and technologies to drive progress, such as new antiviral medicines and improved diagnostic techniques.

Interventions

Vaccination

Hepatitis A, B, and E can all be prevented via vaccination, with many countries implementing large-scale, effective vaccine programs. Globally, the coverage of infant third (full) dose vaccination against hepatitis B was 82% in 2015. The strategy aims to increase the figure to 90% by 2020 and maintain that level until 2030 by widening infant and birth-dose programs, and specifically targeting at-risk populations. In some areas, the hepatitis A vaccine should also be adopted into infant vaccination programs.

Reducing vertical (mother-to-baby) transmission

In highly endemic areas, mother-to-baby is the leading cause of hepatitis B transmission, but it can be effectively prevented if the infant received a birth dose vaccine within 24 hours of birth. To ensure elimination of vertical transmission, a comprehensive approach including education and testing during pregnancy and birth dose vaccination.

In 2015, only 38% of countries used effective methods to prevent transmission. The WHO aimed to increase this to 50% in 2020 and 90% by 2030.

Improving safety

In the absence of safe, high-quality transfusion services, the risk of transmission of hepatitis B and C via contaminated blood products is high. Whilst providing safe blood products is a vital public health responsibility of every government, in 2015 89% of countries provided safe services. The strategy aimed to increase this to 90% by 2020, with a target for 100% of countries to provide national quality-assured blood services by 2030.

An area with significant scope for improvement is with regards to safe injections. Currently, only 5% of injections administered globally use safety-engineered devices such as needle guards or retractable needles. These safety features significantly reduce the risk of needle-stick injuries, and as such, the WHO aimed for this to increase to 50% of injections by 2020, and 90% by 2030.

Finally, by providing harm reduction services for people using injectable drugs, a host of blood-borne infections including hepatitis could be prevented. A comprehensive package of support for people who inject drugs was suggested, including vaccination, opiate substitution programs, and needle and syringe programs.

Progress by 2020

Although the hepatitis elimination strategy will continue for another 9 years, progress against the interim targets set for 2020 can provide insight into the feasibility of the strategy achieving its aims. One study which included 45 high-income countries found that 80% of the target were not on track to meet the 2030 goal, with two-thirds of the sample requiring at least 20 more years to do so. It is highly likely therefore that lower-income countries would be even further from achieving the WHO targets.

References:

- https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/246177/WHO-HIV-2016.06-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Cox, A. L., El-Sayed, M. H., Kao, J. H., Lazarus, J. V., Lemoine, M., Lok, A. S., & Zoulim, F. (2020). Progress towards elimination goals for viral hepatitis. Nature reviews. Gastroenterology & hepatology, 17(9), 533–542. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-020-0332-6

- Waheed, Y., Siddiq, M., Jamil, Z., & Najmi, M. H. (2018). Hepatitis elimination by 2030: Progress and challenges. World journal of gastroenterology, 24(44), 4959–4961. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i44.4959

- https://www.who.int/hepatitis/news-events/07_towards-elimination-Dr-Gottfried-Hirnschall.pdf?ua=1

Last Updated: Jul 27, 2021

Written by

Clare Knight

Since graduating from the University of Cardiff, Wales with first-class honors in Applied Psychology (BSc) in 2004, Clare has gained more than 15 years of experience in conducting and disseminating social justice and applied healthcare research.

Source: Read Full Article