A nasal antiviral created by researchers at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons blocked transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in ferrets, suggesting the nasal spray also may prevent infection in people exposed to the new coronavirus.

The compound in the spray—a lipopeptide developed by Anne Moscona, MD, and Matteo Porotto, Ph.D., professors in the Department of Pediatrics and directors of the Center for Host-Pathogen Interaction—is designed to prevent the new coronavirus from entering host cells.

The antiviral lipopeptide is inexpensive to produce, has a long shelf life, and does not require refrigeration. These features make it stand out from other antiviral approaches under development, including monoclonal antibodies. The new nasal lipopeptide could be ideal for halting the spread of COVID in the United States and globally; the transportable and stable compound could be especially key in rural, low-income, and hard-to-reach populations.

A preprint of the study appeared in bioRxiv on Nov. 5; a paper describing a first generation of the compound and its effect in a 3-D model of the human lung first appeared in the journal mBio on Oct. 20. In this human lung model, the compound was able to extinguish an initial infection, prevent spread of the virus within the lung, and was not at all toxic to the airway cells.

Ferrets a model for respiratory diseases

Ferrets are often used in studies of respiratory diseases because the lungs of these animals and humans are similar. Ferrets are highly susceptible to infection with SARS-CoV-2, and the virus spreads easily from ferret to ferret.

In this study, 100% of the untreated ferrets were infected by their virus-shedding cagemates, approximating a setting like sharing a bed or close living conditions for people.

Moscona and Porotto have previously created similar lipopeptides—small proteins joined to a cholesterol or tocopherol molecule—to prevent infection of cells by other viruses, including measles, parainfluenza, and Nipah viruses. These anti-viral compounds have been challenging to bring to human trials, in large part because the infections they prevent are most prevalent or serious in low-income contexts.

When SARS-CoV-2 emerged earlier this year, the researchers adapted their designs to the new coronavirus. “One lesson we want to stress is the importance of applying basic science to develop treatments for viruses that affect human populations globally,” Moscona and Porotto say. “The fruits of our earlier research led to our rapid application of the methods to COVID-19.”

Lipopeptides prevent viruses from infecting cells

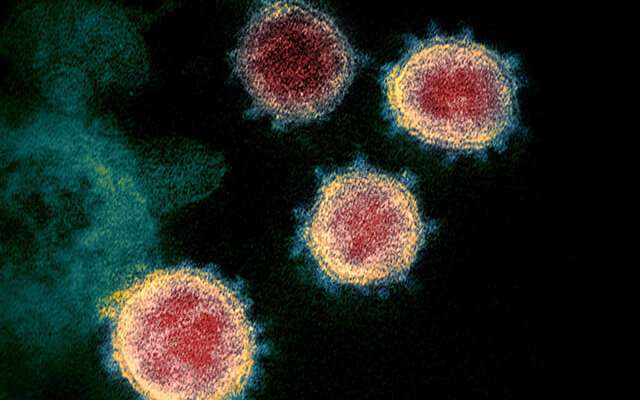

The lipopeptides work by preventing a virus from fusing with its host’s cell membrane, a necessary step that enveloped viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, use to infect cells. To fuse, the new coronavirus unfolds its spike protein before contracting into a compact bundle that drives the fusion.

The compound designed by Moscona and Porotto recognizes the SARS-CoV-2 spike, wedges itself into the unfolded region, and prevents the spike protein from adopting the compact shape necessary for fusion.

In the ferret experiments, the lipopeptide was delivered into the noses of six ferrets. Pairs of treated ferrets were then housed with two control ferrets that received a saline nasal spray and one ferret infected with SARS-CoV-2.

After 24 hours of intense direct contact among the ferrets, tests revealed that none of the treated ferrets caught the virus from their infected cagemate and their viral load was precisely zero, while all of the control animals were highly infected.

Lipopeptides are easily administered

Moscona and Porotto propose these peptides could be used in any situation where an uninfected person would be exposed, whether in a household, school, health care setting, or community.

“Even in an ideal scenario with large segments of the population vaccinated—and with full trust in and compliance with vaccination procedures—these antivirals will form an important complement to protect individuals and control transmission,” Moscona and Porotto say. People who cannot be vaccinated or do not develop immunity will particularly benefit from the spray.

The antiviral is easily administered and, based on the scientists’ experience with other respiratory viruses, protection would be immediate and last for at least 24 hours.

Source: Read Full Article