When I first went from a sedentary, pack-a-day smoker with an awful diet to a lean ultramarathon runner, thanks largely to cannabis edibles, I thought I was the only one. Turns out, I was part of a larger trend of exercisers—at every level—who are using pot to make exercise not just a necessary chore but actually fun. And once I started talking about my own cannabis-fueled epiphany about working out, I found that others were only too happy to share their own stories with me.

Over the course of four years, I spoke with dozens of professional athletes from ultrarunning, cycling, basketball, football, rock climbing, hockey, MMA, Ironman, para-athletics and bodybuilding, aerobics, strength training, hiking, surfing, skateboarding, snowboarding, and many others, about how they use cannabis in their training, competition and recovery.

It was fascinating to me that so many professional and recreational athletes were using cannabis, and yet the phenomenon was so underreported. And when so many of them were describing the same sensation I was feeling from blending cannabis and running—reduction of pain, uptick in mood, a dialed-in playfulness and absence of toxic competition—I knew there was a story that urgently needed to be told.

“A large number of the elite runners are toking up; I’d say most of them,” ultramarathon champion Avery Collins told me. “There’s no other feeling like it in the world.”

Former Philadelphia Flyers enforcer Riley Cote tells me that at least half of the National Hockey League players, are using cannabis—and if widened to also include CBD products, that number jumps to around 90%.

A number of Ultimate Fighting Championship athletes, like Nate Diaz, Elias Theodorou and Derrick Lewis, proudly confess to getting high. There’s even a stoned jiu-jitsu league, High Rollerz, where fighters share a joint before slamming each other to the mat.

And it’s not just current players. Iconic football names like Brett Favre and Joe Montana have entered the cannabis biz, as have NBA legends like Isiah Thomas, Magic Johnson, Al Harrington, Cliff Robinson, and Kevin Durant. Baseball MVP Jimmy Rollins has his own line of pre-rolled joints, and revolutionary feminist soccer player Megan Rapinoe is now sponsored by a CBD brand promoted to athletes.

“I hear a lot of people say we need to get ready, that cannabis is coming to the world of sports,” says sports medicine professor Jeff Konin, PhD. “Whenever I hear that, I say, ‘It’s not coming—it’s already here.’” Konin is currently a clinical professor at Florida International University and he’s also a Hall of Fame athletic trainer and physical therapist. In 2018, he encountered a whole lot of athletes asking about whether (and how) to use cannabis.

Athletes are already using it, Konin explains, but “There is a stigma that’s preventing athletes from being open with their doctors about their use, and keeping sports physicians from being educated on what the science is showing us.”

At the time, he didn’t know how to respond.

In the past he could just advise athletes to not take it, due to its illegality. But now he was encountering such a deluge of anecdotal stories from athletes about their cannabis-derived relief from pain, anxiety, insomnia, and so many others ailments that—even though he knew the subject still needed reputable, peer-reviewed clinical studies—there was no way all these people could be experiencing the same placebo effect.

“The overwhelmingly popular consensus voice of those athletes using cannabis is that they can notice improvements in recovery, and that translates to their performance,” Konin said.

Once legalization began to sweep the nation and dispensaries started popping up like Starbucks, he found that athletes were using cannabis in training and recovery to great effect—and he knew that simply telling them “no” wasn’t an option. Though there was a whole cat’s-cradle of legal and ethical conundrums for a sports medicine educator promoting cannabis.

“Should I encourage my patients to try some low-dose THC?” Konin asked. “Logically, I thought yes, but legally I couldn’t. And that’s what made me want to dig into the science.”

But what is the science on cannabis?

Given its variety of (sometimes conflicting) effects, cannabis can be difficult to classify as a stimulant, tranquilizer, sedative, or hallucinogen—and therefore it’s challenging to evaluate it in the same way. Konin prefers to examine cannabis treatment not through the plant itself but through its impact on the endocannabinoid system (which regulates nearly all bodily functions, like sleep, pain, mood and appetite).

The tricky thing is that cannabis doesn’t affect the body in the same way a traditional performance enhancer like, say, a steroid does. “There’s clear evidence that steroids will increase the size of your muscle and the power you can produce beyond your natural limits, and that’s what makes it a performance enhancer,” he explains. But that’s not how cannabis works. Rather, “the endocannabinoid system returns you to a state of balance after you’ve been depleted.”

Since it’s universally agreed that the human endocannabinoid system is involved in nearly all biological functions—from sleep, appetite and mood, to fertility, immune system, pain sensation and memory—and that cannabis is the ideal tool to influence this system, researchers have been discovering new ways that the plant can be used to reduce inflammation, manage pain, and change the mindset of an anxious athlete (burdened by fame, past injuries, and performance nerves) to one of a playful, confident warrior ready to take on whatever is thrown at them.

When viewed this way, Konin says, it’s ridiculous to classify it in the same league as other performance-enhancing substances, as the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) currently does. “When you don’t have endocannabinoids functioning properly in your body, it’s no different than a lack of insulin for diabetics or ice for an injury. When I put ice on an athlete’s injured ankle, I’m returning that ankle to balance, not taking it beyond its natural limits.” He sees an athlete’s use of cannabis as akin to “addressing a medical condition, not enhancing performance.”

But even if science and society are starting to come around to the use of cannabis as a healthier (and possibly more effective) tool for pain management, recovery and mental health treatment, than pharmaceutical drugs, WADA (charged with monitoring the fight against drugs in sports) doesn’t yet agree. In 2011, WADA clarified that cannabis was indeed considered a performance enhancer, conducting a study with the (historically anti-pot) National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) that found marijuana “can cause muscle relaxation and reduce/decrease anxiety and tension pain during post-workout recovery.” They further explained that it can increase focus and risk-taking behaviors, allowing athletes to forget bad falls or previous trauma in sport, and push themselves past those fears in competition.”

That doesn’t sound all bad to me. But WADA has the final say. Just ask Sha’Carri Richardson, who was forbidden from participating in the 2020 Olympics after using cannabis before the U. S. Olympic trials in June 2021.

“Cannabis should be taken off the banned list,” says former Olympic triathlete and epidemiology researcher, Joanna Zeiger. “When it comes to steroids or human growth hormones, I don’t put cannabis in that category. Is it performance enhancing? Maybe indirectly, because it helps you sleep and eases anxiety and pain. But there are other substances that do the same thing that aren’t banned but are more dangerous, like Motrin and other anti-inflammatories. Athletes pop those like candy while they’re racing, and that dehydrates you and is harmful to your gut. And there are medications for depression or anxiety that help performance, which aren’t banned.”

Following a nasty cycling accident that drove her to retirement in 2009 (along with an autoinflammatory disease) Joanna was plagued with severe chronic pain, insomnia, nausea, muscle spasms, and difficulty breathing. After experimenting with cannabis, Joanna had her first pleasant night’s sleep in years, and found that it did wonders for her pain, appetite, and muscle spasms.

Joanna launched the nonprofit Canna Research Foundation with the intention of assembling data that could be used by medical professionals and patients considering if and how cannabis could be used for various ailments.

“Anecdotally, I’ve heard from a lot of people who had anxiety about going to the gym, and they’d consume cannabis and it would allow them to put all that aside and do their workout,” she tells me.

Where we are now

Jeff Konin doesn’t believe that the world of sports medicine and WADA are going to change their tune until heftier science is on the table (which isn’t happening until it’s federally legalized, which won’t happen until there’s heftier science on the table, and so on). But he does believe that we’re in the middle of a deluge of athletes using cannabis products with promising results—and that the more open they are about this, the more recreational athletes will begin using them, creating an even greater demand for his type of work.

“Whatever the pros do—whether it’s Breathe Right nasal strips or Gatorade—it trickles down to the rest of the population,” he says. “Soon you’re going to have more athletes coming out about their use, and even endorsing products, and then it’s all over.”

In 2011, WADA released a report on cannabis prohibition. Buried toward the bottom is a section titled “The Spirit of the Sport,” which says that the term is “difficult to define” and “does not rely on established scientific facts.”

“The consumption of cannabis and other illegal drugs contradicts fundamental aspects of the spirit of sport criterion. The international anti-doping community believes that the role model of athletes in modern society is intrinsically incompatible with use or abuse of cannabis…Use of illicit drugs that are harmful to health and that may have performance enhancing properties is not consistent with the athlete as a role model for young people around the world.”

Bingo. It’s not that cannabis offers one athlete an unfair advantage over another; it’s that kids may get the wrong idea. The right idea, as my understanding of this statement implies, was articulated most succinctly by former attorney general Jeff Sessions when he opposed legalization efforts by saying, “Good people do not smoke marijuana.”

Ultimately, there is little consistent messaging as to why cannabis is banned in professional sports.

The one common undertone to all of these scandals is the moralistic finger wagging toward seemingly “good” people (sports stars) doing a previously assumed “bad” thing (getting high)—with little explanation beyond a patronizing “because I said so.”

This nebulous stance against pot has resulted in serious damage to professional athletes’ careers, while forcing them to take much more harmful, addictive substances that—for whatever reason—are not banned. To deny sports stars access to a substance humans have been consuming (with terrific results) for thousands of years remains one of the many insidious threads the war on drugs continues to inflict on the American public. It’s high time we rid ourselves of these antiquated policies and bring pro sports into the 21st century.

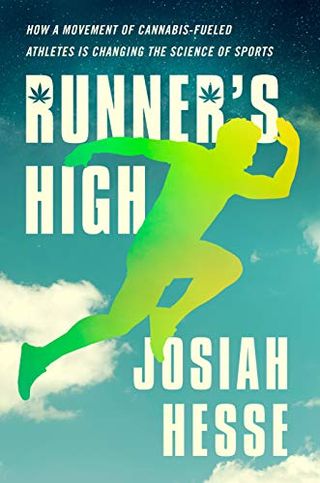

Adapted From Runner’s High by Josiah Hesse, published by G.P. Putnam’s Sons, an imprint of the Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Bear One Holdings, LLC.

Source: Read Full Article