Right now, drug companies and university-based teams are working urgently to find and test new medications that could prevent or slow the decline of brain function in older adults. But a new study suggests they’ll need to work harder to find volunteers for their clinical trials. The work is published in the Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Only 12% of people between the ages of 50 and 64 say they’re very likely to step forward to test a new dementia-prevention drug, though another 32% say they’re somewhat likely, according to the new findings published by a team from the University of Michigan.

Those who have a family history of Alzheimer’s disease or another form of dementia, or who believe they’re likely to develop dementia, are more than twice as likely to say they’d sign up to test a new drug. So are those who have talked about dementia prevention with a doctor—but they accounted for only 5% of those surveyed.

The data for the study came from the National Poll on Healthy Aging, based at the U-M Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation with support from AARP and Michigan Medicine, U-M’s academic medical center.

Researchers from the U-M School of Public Health did an in-depth analysis of the responses from a national sample of more than 1,000 adults in their 50s and early 60s.

“With Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia affecting millions of older Americans and their families, and costing hundreds of billions of dollars in care, finding new options for preventing and slowing cognitive decline is a critical national goal,” says Scott Roberts, Ph.D., the poll’s associate director and a professor at the School of Public Health. Roberts is the leader of the Outreach, Recruitment & Engagement Core at the Michigan Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

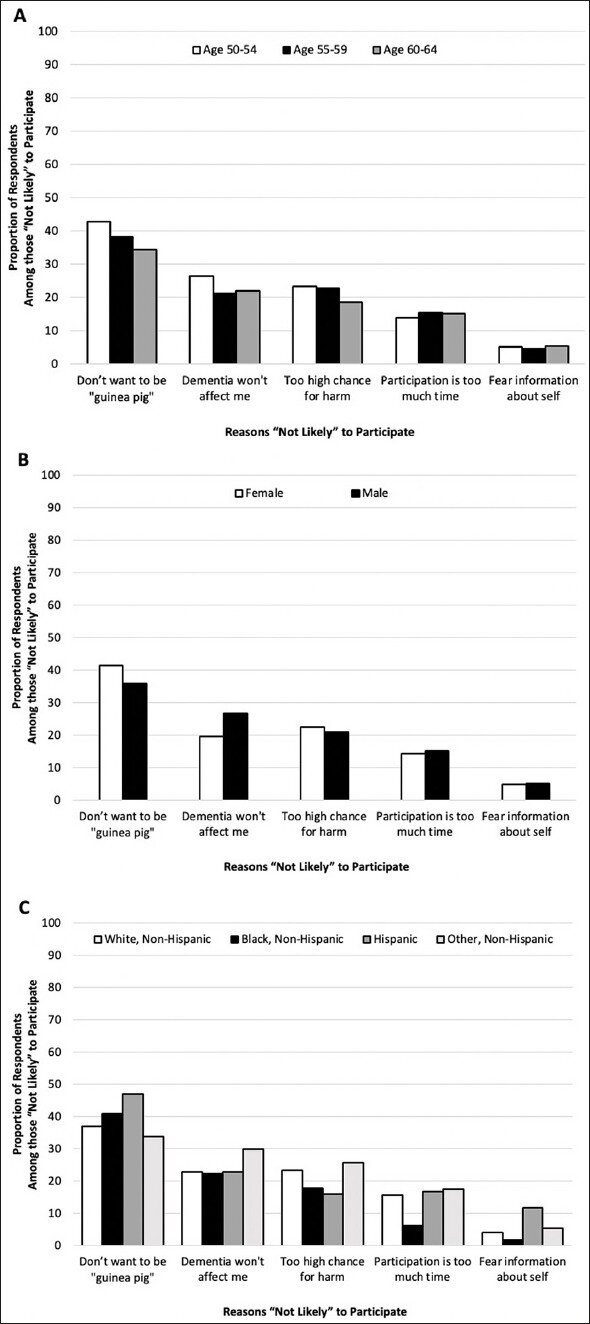

“Our analysis shows that the 56% of respondents who say they’re not likely to take part in a dementia prevention drug trial mainly cite concerns over being a ‘guinea pig’ or the potential for harm, but nearly 1 in 4 said it’s because they don’t think dementia will affect them,” says Chelsea Cox, M.P.H., M.S.W., the first author of the new study and a doctoral student in public health. “However, as other research has shown, one-third of people over 65 have dementia or mild cognitive impairment, and the rate rises steadily with age.”

The authors note that current drug trials for dementia prevention often fail to recruit a nationally representative pool of participants. This means that the results of such studies used to seek approval to market new treatments may not accurately represent the drugs’ performance across different racial and ethnic groups.

The lack of willingness to participate in prevention trials seen in the new study wasn’t because older adults are in denial about dementia.

Half said they think they’re at least somewhat likely to develop dementia, and 66% said their memory was slightly or much worse than it had been when they were younger. One-third had a family history of dementia, and 18% had cared for someone with dementia.

The poll questions used for the study made it clear that taking part in a clinical trial of a prevention medication does not cost participants anything financially. But another type of cost—time—concerned 15% of those who said they would not take part in a study.

Cox and Roberts hope the results will be used by those designing clinical trials to inform recruitment and informed consent materials aimed at prospective participants.

Prioritizing those with a family history or a perceived personal risk for dementia might be beneficial, along with encouraging more clinicians to talk with their patients about reducing risk for dementia and taking part in studies. But communicating about the safety of trials, and minimizing the burdens involved for participants, could also be key.

Source: Read Full Article