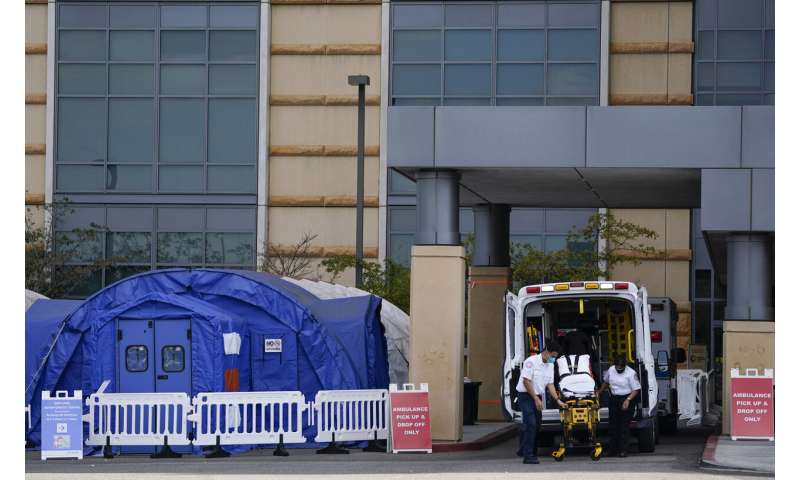

Ambulances waited hours for openings to offload coronavirus patients. Overflow patients were moved to hospital hallways and gift shops, even a cafeteria. Refrigerated trucks were on standby, ready to store the dead.

For months, California did many of the right things to avoid a catastrophic surge from the pandemic. But by the time Gov. Gavin Newsom said on Dec. 15 that 5,000 body bags were being distributed, it was clear that the nation’s most populous state had entered a new phase of the COVID-19 crisis.

Now infections have been racing out of control for weeks, and California has routinely set new records for infections and deaths. It remains at or near the top of the list of states with the most new cases per capita.

Experts say a variety of factors combined to wipe out the past efforts, which for much of the year held the virus to manageable levels. Cramped housing, travel and Thanksgiving gatherings contributed to the spread, along with the public’s fatigue amid regulations that closed many schools and businesses and encouraged—or required—an isolated lifestyle.

Another factor could be a more contagious variant of the virus detected in Southern California, although it’s not clear yet how widespread that may be.

California’s woes have helped fuel the year-end U.S. infection spike and added urgency to the attempts to beat back the scourge that has killed more than 340,000 Americans. Even with vaccines becoming available, cases are almost certain to continue growing, and yet another surge is expected in the weeks after Christmas and New Year’s.

The southern half of the state has seen the worst effects, from the agricultural San Joaquin Valley to the Mexico border. Hospitals are swamped with patients, and intensive care units have no more beds for COVID-19 patients. Makeshift wards are being set up in tents, arenas, classrooms and conference rooms.

Hospitalizations statewide have gone up more than eightfold in two months and nearly tenfold in Los Angeles County. On Thursday, the total number of California deaths surpassed 25,000, joining only New York and Texas at that milestone.

“Most heartbreaking is that if we had done a better job of reducing transmission of the virus, many of these deaths would not have happened,” said Barbara Ferrer, the county’s public health director, who has pleaded with people not to get together and worsen the spread.

Crowded houses and apartments are often cited as a source of spread, particularly in Los Angeles, which has some of the densest neighborhoods in the U.S. Households in and around LA often have several generations—or multiple families—living under one roof. Those tend to be lower-income areas where residents work essential jobs that can expose them to the virus at work or while commuting.

The socioeconomic situation in LA County is “like the kindling,” said Paula Cannon, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Southern California. “And now we got to the stage where there was enough COVID out in the community that it lit the fire.”

Home to a quarter of the state’s 40 million residents, LA County has had 40% of the state’s deaths and a third of its 2.2 million cases. The virus has hit Latino and Black communities harder.

Cannon said there’s a moral imperative for people who can follow stay-home orders to help prevent spread that is harder to contain in other areas.

“What you can’t do is say to people, ‘Can you stop living in a house with eight other people, five of whom are working essential worker jobs?'” she said. “This is the structure that we can’t change in LA. This is, I think, contributing to why our levels have suddenly got scarily high and looks like they’re going to keep going up and keep staying that way.”

In March, during the early days of the pandemic, Newsom was hailed for issuing the nation’s first state stay-home order.

The Democrat eased business restrictions in May, and when a broader restart led to another surge, imposed more rules. In early December, with cases out of control, he issued a looser stay-home order. He also closed businesses such as barbershops and salons, halted restaurant dining and limited capacity in retail stores. The latest restrictions apply everywhere except in rural Northern California.

But Dr. Lee Riley, an infectious diseases professor at the University of California at Berkeley, said that while the state managed to flatten the curve of rising cases, it never effectively bent the curve downward to the point infections would die out.

When cases rose in June and July, California was never able to do enough contact tracing to isolate infected people and those they may have exposed before they spread the disease—often unwittingly—to others, he said. And public health directives were never adequately enforced.

“What California did was to maybe delay the peak,” Riley said. Infections “really just never got low enough. And we started lifting the restrictions, and that just allowed the transmissions to just continue to increase. We never really saw a real decline.”

California’s health secretary, Dr. Mark Ghaly, said if state and local leaders had not made difficult decisions early on that saved lives, the current surge might not be the worst the state has seen.

He acknowledged the exhaustion many people feel after enduring months of disruptions to their lives. Public health officials, he said, need to find a way to reach people who have given up or not followed rules on social distancing and masks.

Across California, local officials have reminded people that the fate of the virus lies in their behavior and asked for one more round of shared sacrifice. They reminded people that activities that were safe earlier this year are now risky as the virus becomes more widespread.

Source: Read Full Article