Stanford Medicine researchers have discovered a possible new way to treat pain without the use of opioids. By targeting a specific area of a well-known pain receptor, they were able to reduce pain sensitivity in mice without affecting the receptor’s other functions, such as sensitivity to heat.

Their inspiration? Chickens.

Many chicken farmers know that squirrels and mice won’t eat chicken feed laced with capsaicin—the chemical that gives chili peppers their spiciness. In mammals, capsaicin activates a pain receptor to cause a burning sensation. In most bird species, capsaicin has little effect.

“It turns out that birds are naturally resistant to capsaicin,” said Eric Gross, MD, Ph.D., associate professor of anesthesiology, perioperative and pain medicine.

That fact prompted Gross to wonder whether it was possible for humans to have a genetic variant that made the receptor, known as transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1, or TRPV1, more birdlike—and more resistant to pain.

In a study to publish Feb. 1 in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, Gross’s team and international collaborators identified a specific genetic variant of TRPV1 that reduces pain sensitivity in humans. Though this variant is extremely rare, the researchers were able to replicate the effects of the altered gene with a custom-designed drug.

Can’t touch this

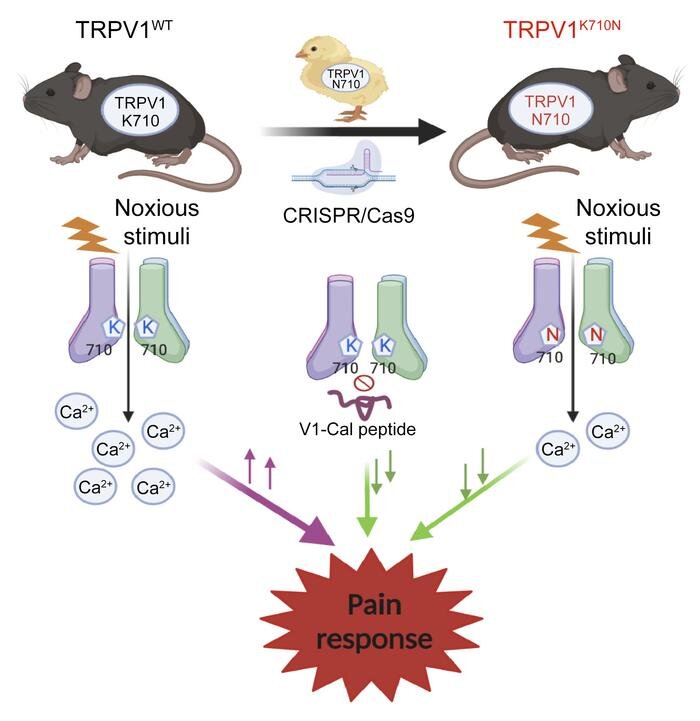

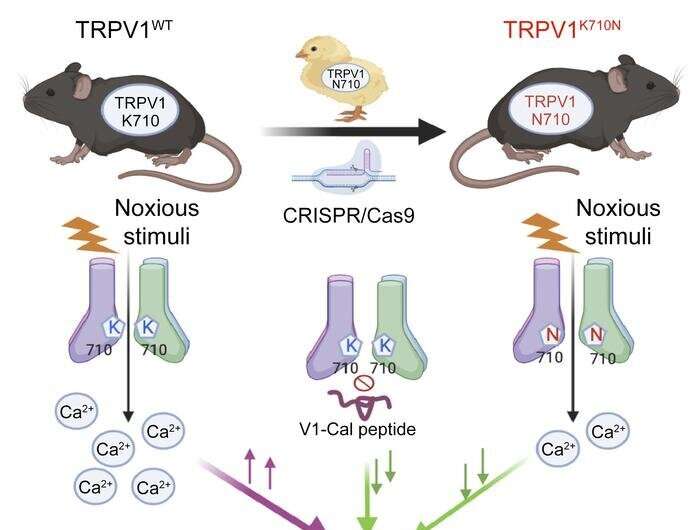

The researchers first used a computational approach to find genetic variants of human TRPV1 that resemble avian TRPV1. When they tested these variants in genetically modified cells, one variant, known as K710N, drastically reduced the receptor’s reaction to capsaicin.

“We were quite amazed that there was such a decrease in activity of TRPV1’s response to capsaicin when we made that genetic variant,” said Gross, who is the senior author of the study. “It was to the point where we actually tried this several times to make sure that was really what we were seeing.”

Next, they used the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technique to create mice with the K710N mutation. The plan was to see if these mice would find palatable the capsaicin-laced bird food that normal mice reject. The response was more immediate than the researchers expected: As soon as the spicy bird food was placed on the floor of their cage, normal mice lifted their paws as much as they could to avoid touching the capsaicin—suggesting that even skin contact caused pain. The K710N mice, meanwhile, lifted their paws much less frequently and were comfortable enough with the capsaicin to sample some spicy bird food.

Based on these and other behavioral responses, Gross estimates that the mutation reduced pain by about 50%.

Dialing down pain

The TRPV1 receptors in our sensory neurons do more than generate a burning sensationwhen we eat chili peppers. They also respond to other stimuli such as heat and physical injury—playing an important role in protecting us from danger—and they regulate body temperature.

“You don’t want to take away the full sensation of pain,” Gross said. “You still want to have somebody, if they place their hand over a hot stove or step on a Lego, to have that pain sensation.”

The K710N mice enjoyed a happy medium—they felt less pain but could still sense harmful stimuli and maintain normal body temperatures. “We were able to dial it down rather than take it away completely,” Gross said.

TRPV1 has yet more functions throughout the body, such as protecting against organ damage. The researchers found that the K710N variant retained and even enhanced these protective benefits of TRPV1. Heart cells with the variant, for example, were less likely to die when temporarily deprived of oxygen.

Custom-made drug

With an understanding of precisely how the K710N mutation changed the structure and function of TRPV1, the researchers were able to design a drug that had the same effect. When they gave the drug, a peptide named V1-cal, to mice by injection or infusion, it reduced their sensitivity to capsaicin and lessened chronic pain from nerve injury. Just like the K710N mutation, the drug had little impact on heat sensation and regulation of body temperature.

Compared with previous attempts at treating pain by targeting TRPV1, the new chicken-inspired drug works more selectively, with fewer side effects.

“People have always used a direct approach, so they looked at ways to specifically activate or block the receptor,” Gross said. “That’s been a challenge because activation of the receptor causes pain, while inactivation may cause unwanted changes in body temperature.”

A high concentration of capsaicin activates and eventually desensitizes the receptor, and has been used in analgesic creams or patches, but the treatments increase pain before reducing it. On the other hand, drugs that block the receptor have failed in clinical trials because they caused people to overheat.

“Instead of directly activating or inactivating the receptor, the drug we developed modulates only a specific area of the receptor,” he said. “We’re able to avoid the side effects that have been plaguing drug discovery for TRPV1 for quite some time.”

Gross’s team hopes to modify the peptide so that it is more stable and can relieve pain longer. In the study, the mice were given the drug by continuous infusion.

As an anesthesiologist, Gross often treats patients with post-operative pain. “We’re really excited to see if this is a potential therapeutic for pain after surgery, and to help us move toward an opioid-free approach.”

More information:

Shufang He et al, A human TRPV1 genetic variant within the channel gating domain regulates pain sensitivity in rodents, Journal of Clinical Investigation (2022). DOI: 10.1172/JCI163735

Journal information:

Journal of Clinical Investigation

Source: Read Full Article