Approximately one in forty-two thousand children are born with a disease called CDKL5 Deficiency Disorder, according to a new medical report recently published in the journal Brain and presented last month at the 13th European Paediatric Neurology Society Congress in Athens, Greece. This means that each year there are over 100 new children born with the disease in the EU alone, and over 3,000 in the world.

The disease leads to frequent seizures shortly after birth and severe impairment in neurological development, with most affected people being unable to walk, talk or care for themselves. “When our daughter was diagnosed in 2009 they told us there were approximately 200 cases in the world”, says Carol-Anne Partridge, chair of CDKL5 UK and the International CDKL5 Alliance, which represents patient organizations from 18 countries. “Today we know that these children were simply not being diagnosed correctly,” she adds.

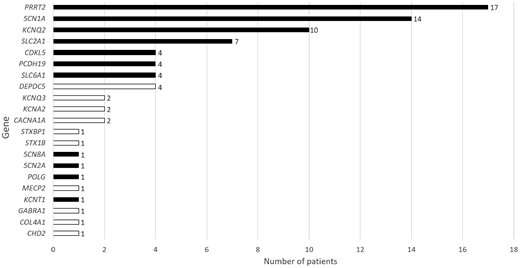

The study, by a medical team from the Royal Hospital for Children in Glasgow, kept track of all births in Scotland during three years and applied genetic testing to all children under 3 years of age who developed epilepsy. “We found that as many as 1 in 4 children with epilepsy have a genetic syndrome”, explains Professor Sameer Zuberi, corresponding author for the study, “and a small group of genes explains most of the cases.”

Among these genes is CDKL5, which encodes a protein necessary for proper brain functioning. Mutations in the CDKL5 gene produce CDKL5 Deficiency Disorder, with one of the first symptoms being early-onset epilepsy. There is no therapy approved for treating the disease now known to affect thousands of people.

But therapies are being developed and the disease has recently attracted much interest from the pharmaceutical industry. There are four clinical trials currently ongoing, and additional companies have announced efforts towards the development of enzyme replacement and gene therapies.

The new disease incidence study highlights the need to increase disease awareness around these genetic disorders previously thought to be much more rare. “Our data suggest that genetic testing should be a primary investigation for epilepsies presenting in early childhood,” explains Professor Sameer Zuberi.

Most of these cases are due to de novo (spontaneous) mutations, so they can occur in any family. But genetic testing is not offered to many patients with early childhood epilepsy and neurodevelopmental disabilities. Because of that, only about 10% of all people living with CDKL5 Deficiency Disorder might have a correct diagnosis.

Source: Read Full Article