You’ve probably done pushups, pullups, squats, and situps, but chances are you’ve never done a move like this: Kneel on your shins, abs tight, a single kettlebell held overhead in your left hand. Eyes on the kettlebell, twist your torso and bend forward, letting your right elbow scrape the ground. Then press back up.

You’ve just done a windmill, a little-known (and diabolical) exercise that has as many muscle-building, fat-blasting benefits as numerous better-known moves. The windmill also makes you do something you probably don’t do enough: rotate. “Your everyday life demands constant rotation,” says David Otey, C.S.C.S., a Men’s Health training advisor. “Nobody walks robotically in straight lines; you’re twisting, turning. You bend over to the side to pickup a bag or twist to grab that thing you left on the counter.”

Your typical workout lacks this twist. Most exercises teach you to eliminate all rotation (see far right), tightening abs and glutes to build ever-important core stability. Often you’re moving both arms at the same time (as you do during pushups) or both legs in the same pattern (as you do during deadlifts and squats).

Rotational exercises break that pattern—and are the perfect elixir for a quarantine gym life that’s been Groundhog Day boring. Suddenly, each arm and each leg has a different task, and your hips must rotate one way while your shoulders turn the other. Sure, these moves can be challenging, but they generate serious strength and power.

How Rotational Exercises Got a Start

Fighters and other athletes have used rotational movements for “hundreds if not thousands of years,” says Otey, even if they weren’t always about fitness. The discus throw, a competitive sport since the eighth century B.C., is one of the earliest examples of rotational power in athletics. It requires competitors to twist backward, then rotate forward to heave the disc as far as possible.

Modern rotational training’s renaissance started about 15 years ago, when Juan Carlos Santana, a functional-training veteran and founder of the Institute of Human Performance in Boca Raton, Florida, detailed what he called the “serape effect” in a Strength and Conditioning Journal paper. Instead of viewing your abs as your “core” muscles, Santana described your core as a series of connected muscles running diagonally up the front of your torso, over your shoulders, then across your back and down the front of your body.

This pattern, which resembles a traditional serape blanket when worn as a garment, essentially links your right shoulder to your left hip (and left shoulder to right hip). Twisting your body helps you utilize these interconnected muscles, which fire as a unit to assist you in even the simplest of tasks. They are active in helping you reach across your body to buckle your seat belt, and they power you to roll out of bed first thing in the morning. Innovative trainers working with pro athletes took note of Santana’s work, and over the years the exercises trickled into the mainstream.

Rotate Like You Mean It

Even basic movements require small amounts of rotation, says MMA trainer Brandon Harris, who’s worked with fighter Sean O’Malley. Truth be told, even when you walk, your pelvis rotates slightly with each step. “We are rotational,” Harris says. “So when we walk, we rotate. When we throw, we rotate.”

The more athletic and explosive your task, the more you can benefit from generating rotational power. That’s why baseball batters rotate with such aggression and velocity during every at-bat. And MMA fighters, who must generate maximum power on every punch or kick, rely on rotational movements even more. Think of a fighter throwing a right cross, planting both feet, pivoting on his right, twisting his right hip back and to the left, then driving it all forward to deliver his punch, essentially activating all his serape muscles.

You may not need to knock anyone out, but you can still get a lot out of adding rotational exercises to your training, because they challenge different muscle groups (think abs and lats) to work together.

You’re readying your body to perform better during classic strength lifts like squats and bench presses—and you’re improving your coordination as well.

“Doing rotational exercises gives you more fluidity and smoother movement,”says Harris. Start with the ones above.

The Big Little Question: So, What’s Anti-Rotation?

Try This Now: Get in a plank. Lift your right arm. Your right shoulder will collapse toward

the floor—unless you tighten your abs and glutes and resist. This resistance is anti-rotation. Your body can create rotation, but it must also stop it.

“If you want to transfer energy, which is rotational power, you need to have the ability to arrest momentum, too,” Otey explains. You rely on the same rotational muscles to halt rotation; you’re simply holding an isometric contraction, forcefully squeezing your muscles to become immovable. “It’s just as important,” he says.

“You need to be able to do both things.”

Expand Your Rotation

Do these 3 moves all together as a changeup full-body session. Or add 1 exercise to the end of your regular workout.

Rotational Split Squat

Stand holding a kettlebell or other weight in front of you. Shift your right foot a few feet behind you. Rotate your torso to the left. Tighten and hold this position. Bend your front knee, lowering until your front thigh is parallel to the ground; press back up. That’s 1 rep; do 3 sets of 10 to 12 per side.

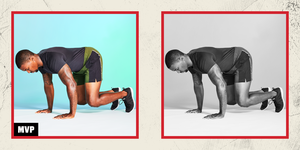

Rotational Plank

Set up in plank position, elbows directly below shoulders, abs and glutes tight. Place your right arm behind your back. Keeping your hips square to the ground, actively rotate your torso up and to the right side. (It doesn’t need to move much.) Return to plank position. That’s 1 rep; do 3 sets of 10 to 12.

Split-Stance Cable Row

Face a cable machine or a wall with resistance bands anchored to it. Set the cables or bands to shin level and grasp the handles. Step your right leg about 2 feet back, bend your knees, and hinge forward slightly, core tight. Step backs lightly so there’s full tension on the bands or cable handles. Keeping your core tight, row your left arm back until your elbow is behind your torso. Return to the start; repeat on the right side.That’s 1 rep; do 4 sets of 10, switching stances every set.

This story originally appears in the December 2020 issue of Men’s Health.

Source: Read Full Article