Researchers from Japan’s Osaka University have made an important leap in our understanding of how chronic pain conditions develop. In a study published on July 25 in Journal of Neuroscience, the team explains how a protein previously implicated in neuron growth and cell adhesion is also critical for the development of pain sensitization.

Neuropathic pain is a chronic condition arising from previous nerve injury or certain diseases, including diabetes, cancer, and multiple sclerosis. Affected patients often display hypersensitivity to normally non-painful stimuli such as touch or repetitive movement, with pain commonly manifesting as shooting burning sensations, numbness, or pins and needles. In many cases, the pain cannot be relieved with analgesics.

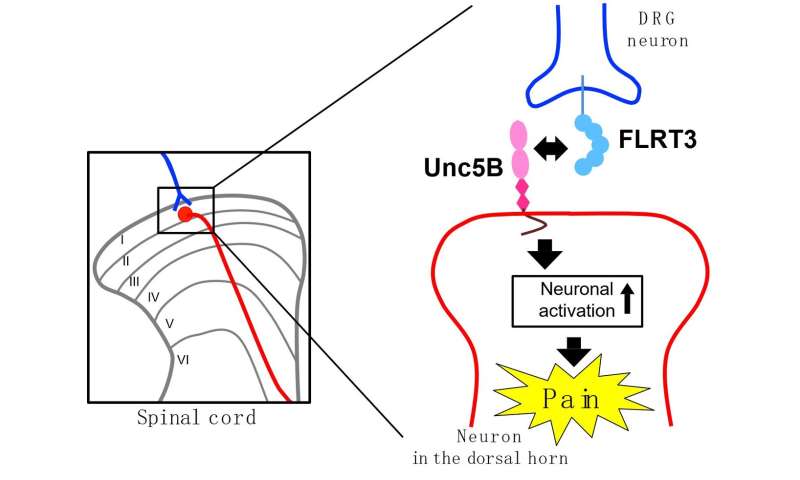

In humans, the spinal cord dorsal horn acts as a sorting station for pain stimuli. Signals coming in from peripheral areas of the body are processed and then transmitted via secondary neurons to the brain. Importantly, this is a key region in the development of neuropathic pain; studies have linked the condition to abnormal neuronal excitability in the spinal cord dorsal horn. However, what causes these neurons to become overly excited remains a mystery.

FLRT3, or fibronectin leucine-rich transmembrane protein-3, is a protein commonly found in both embryonic and adult nervous systems. And while researchers don’t know exactly what role it plays in adult tissues, FLRT3 has been implicated in synapse formation and cell adhesion in the developing brain.

But it was reports of FLRT3 expression in the dorsal horn following nerve injury that led the researchers from Osaka University to investigate the possibility that FLRT3 could be involved in neuropathic pain.

“We examined FLRT3 expression in the dorsal horns of adult rats after peripheral nerve injury,” explains lead author of the study Moe Yamada. “Interestingly, even though Flrt3 gene expression was only observed in the dorsal root ganglion, high levels of FLRT3 protein were found in the dorsal horn.

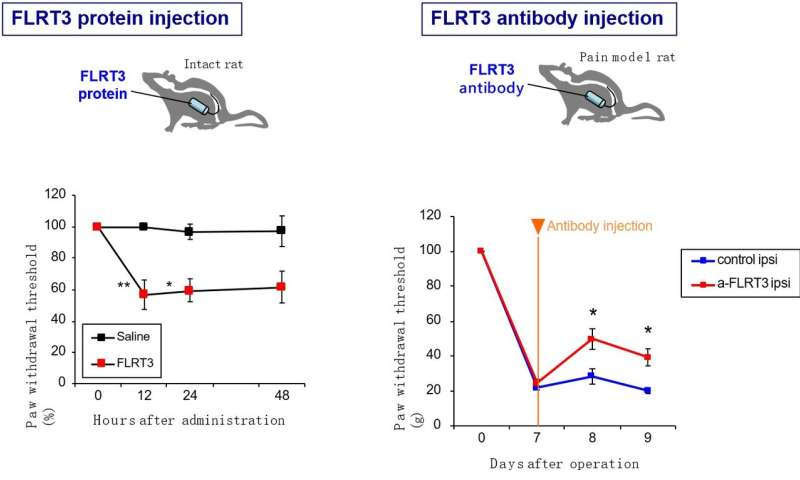

“When we then injected purified FLRT3 into the subarachnoid space so that it reaches the cerebrospinal fluid or overexpressed the protein in the dorsal root ganglion using a viral vector, the treated rats developed touch sensitivity, called mechanical allodynia,” adds Yamada.

Encouragingly, if they then blocked the activity of FLRT3 using antibodies or by gene silencing, the mechanical allodynia symptoms arising after nerve damage all but disappeared.

Source: Read Full Article