Researchers at Karolinska Institutet and from the Netherlands have developed a simple tool that shows the survival probability of a person with dementia over three years. They hope this will facilitate dialog with the most seriously affected patients and help doctors plan necessary care. The study is published in Neurology.

Dementia diseases are currently incurable. There are, however, many kinds of dementia, which develop differently from person to person. Some people can live for many years with their disease, while other conditions progress more aggressively. This means that doctors need a simple tool to indicate the severity of the disease at the point of diagnosis. This can help in planning care and informing patients about how their disease is likely to develop.

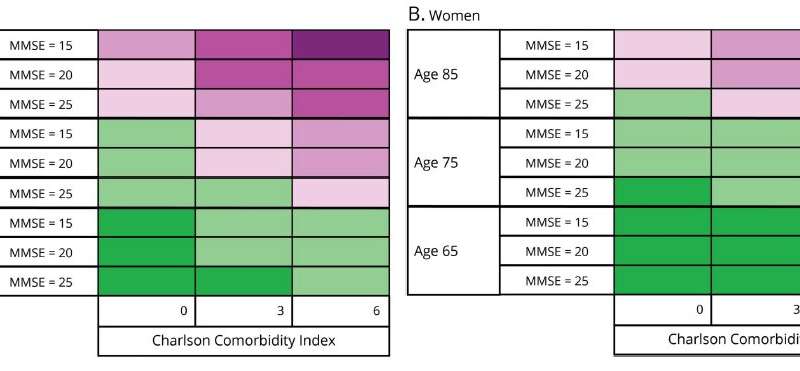

For their study, the researchers monitored patients over the age of 65 who were diagnosed with dementia and registered in the Swedish Dementia Registry between 2007 and 2015. The study included over 50,000 individuals monitored via various health-data registries up to 2016, by which time 20,000 of them had died, on average after a median time of 4.8 years after diagnosis. The researchers examined the effect on post-diagnosis life expectancy of a number of easily identifiable factors, producing two clear, schematic tables.

The first one is for primary care physicians that produces a prognosis based on sex, age, cognitive ability (measured using the MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination) and comorbidity (measured using the Charlson Comorbidity Index).

The second table is for specialist clinics, such as memory clinics, that also factors in the specific subtype of dementia (Alzheimer’s disease, for instance, is often less aggressive). Equipped with these parameters, doctors can place an individual case in the schematic table to show how likely it is that the patient will die within three years of diagnosis.

The tool is intended for use by people who care for or treat dementia patients in primary care or at specialist clinics. One aim is to give doctors and care providers a better understanding of which patients are in urgent need of a care plan and who may benefit from additional monitoring. Another goal is to help doctors and other care providers to engage in a dialog with their patients about their disease and the risk of death.

The study’s corresponding author, Sara Garcia-Ptacek, a neurologist at Stockholm South General Hospital, says that many patients ask about how their disease will progress, and that a tool like this can be useful to help answer those questions.

Source: Read Full Article